Hando Talks Environmental Crimes

On February 27th, a talk about environmental crimes took place in Room 427 of Fairmont State University’s Engineering and Technology Building. Eight students attended, the majority being Occupational Safety majors.

Assistant Professor of Occupational Safety and Occupational Safety Program Coordinator Abby Chapman introduced the speaker, John Hando, to the audience.

John Hando worked in the Department of Natural Resources after graduating from Fairmont State University in the Class of 1987. Later, Hando worked for the Department of Environmental Protection in 1993. Now, Hando is the Risk Assessment and Emergency Response Coordinator at West Virginia University.

In discussing environmental crimes regarding hazardous waste and the liability that comes with improper handling and disposal, Hando prompted students to keep in the mind the question, “How far does liability go?”

The discussion started with a lecture about negligence versus knowingly taking part in environmental crimes against acts like the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act and Resource Conservation and Recovery Act.

Merriam-Webster Law defines negligence as “failure to exercise the degree of care expected of a person of ordinary prudence in like circumstances in protecting others from a foreseeable and unreasonable risk of harm in a particular situation.”

Likewise, knowingly is defined as “having or reflecting knowledge.”

Both negligently and knowingly causing environmental crimes with hazardous waste can result in misdemeanors, felonies, fines and imprisonment.

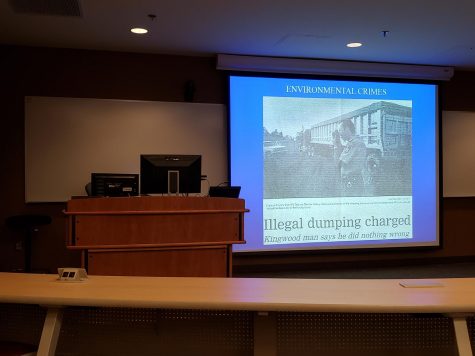

After the lecture, students were asked to participate in the analysis of case studies personally worked on by Hando in his early career. Students analyzed crime scene photos, how those involved were charged and on whom the liability rested.

The first case study Hando discussed was the first hazardous waste case to happen in West Virginia. In this 1990 case, hazardous waste was illegally dumped with permission of a fraudulent hazardous waste manifest—a document tracking hazardous waste.

The second case study analyzed by students was a two year–long investigative case of the illegal activity of a chemical manufacturing company in the northern panhandle of West Virginia.

After analysis of the case studies, Hando remarked on the common denominator of both cases—a paper trail of all illegal activity. “Don’t put anything in writing. If you do, destroy it,” he said sarcastically.

News clipping of the first hazardous waste dumping case in West Virginia.